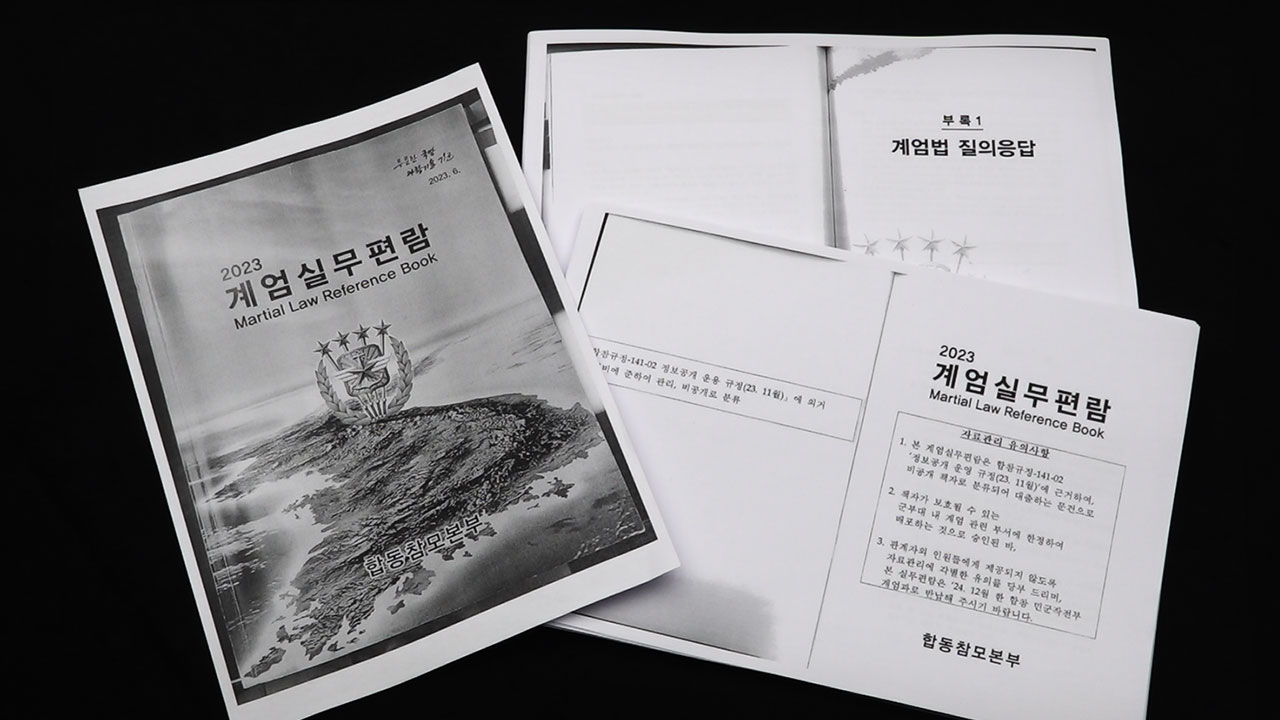

S. Korean Martial Law, A Gag Order to its People and the Press

2024년 12월 20일 13시 02분

A refugee crisis hit Europe in 2015 and its repercussions were noticeable all over the planet: one million people from war-torn Syria made their way, mostly by foot or by boat, through the Aegean Sea and into the continent. At this time, neighboring countries of Syria had already taken in millions of refugees: two million in Turkey, one million in Lebanon, one million in Jordan. When the United Nations cut off funding to the refugee camps and thereby caused a shortage of food and water, it set off a wave of wanderers who could only help themselves but heading off towards Europe, a supposed safe haven.

At this time, Syria was under a heavy civil war. Autocratic ruler Assad’s troops were fighting resurgent forces, or rebel groups. Assad wouldn’t spare his own people, using toxic gas against the population of Syria in order to cast out the rebellion. The United States under President Barack Obama withdrew from their earlier warning that using toxic gas would mean crossing a red line. This was widely interpreted as the turning point for the US to get involved by sending troops or bombing Mr. Assad’s army. As Mr. Obama withdrew, Vladimir Putin rejoiced. Supporting the ruler of Damascus, he could secure Russia’s influence in the region, gaining and maintaining access to the Mediterranean Sea. The unfolding refugee crisis further pleased the Russian rulership, for it was unsettling not only the Middle East but also large parts of Europe. Mr. Assad found a counterpart for his villainous games.

The refugees made their way through the Balkans in the heart of Europe, where they got stuck in Hungary in the late summer of 2015. The destination in mind of this miserable journey for many was Germany, the richest nation in all of Europe. However, by law, the European Union doesn’t deal with refugees in a way that would allow nation states to deliberately choose where they would like to go. On the contrary, the mechanism is: in whatever country a refugee arrives, he or she must be registered and stay until they are redistributed to a different member country of the EU according to a specific measurement of the region. Before the war in Syria, most migrants came from Africa via a dangerous route on a rubber raft. Their point of entry was typically Italy, as well as Spain. Both these countries are in their own perception peninsulas, surrounded by the sea, which makes effective coast guard protection a primary goal of any government.

In the case of the Syrian war, the practice of the European Union would have meant that Greece needed to keep one million refugees until the other EU member states agreed to take in their share of them. This burden would have been overly excessive, and so the governments along the route let the refugees pass until they got stuck in Central Europe, many of them in Hungary.

By then, over the course of 2015, around 80,000 new refugees every month was arriving in Germany. In late August, German Chancellor Angela Merkel took then the decision to let all people into the country that had been trapped in Hungary and on the road there. The influx of these up to 250,000 refugees into Germany was chaotic to say the least: to this very day, it is not entirely certain how many people sought shelter in Germany, claiming they were Syrian. Some of them registered several times under different names, and a large group in fact is not from Syria but from Iraq, Afghanistan, and Somalia. Translators of course notice the difference, but this took time, and the law stated that whoever entered the country has the right to seek asylum and thus cannot be sent back.

In the aftermath of the German Chancellor’s decision, a new right-wing party gained popularity and power – 13% in the last federal election in September 2017. In some regions, the party received between 20 to 30 percent. For the first time since the end of World War II, a right-wing party entered the national parliament in Germany. But not only in Germany: Austria now has a right-wing part of the government. Hungary and Poland have right-wing Prime Ministers. In almost every European country, there are strong right-wing or even extremist parties in parliament, such as in France, the Netherlands, and the UK. Europe is being torn apart by the question of migration and how to tackle it.

The continent has taken on responsibility in the past, believing in human rights and stating in legal documents to uphold these human rights. Also in terms of religion, some say Europe is obliged to help. Pope Francis, the supreme pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church, urged every parish and every monastery in Europe to take in one Syrian refugee family. In majority-Catholic countries such as Poland and Hungary, the governments oppose the demand of the Church but emphasize at the same time that Europe is a Christian continent that needs to remain free from Muslim immigration.

So today, the movement in Europe has taken a clear stance against immigration from Muslim majority countries. This is result of the bad organization during the refugee crisis in 2015 on one hand, and on the other a general fear of being overtaken by alien groups such as the Muslims. At this point, Europe is not alone with this: the United States has not taken in refugees from Syria, nor have Latin American or Asian countries taken in a significant number of refugees.

The global trend goes towards isolation and emphasis of the own while ostracizing the others. "Us versus them” is a very old technique used by populists and autocratic rulership in order to highlight the own group and define other groups as inferior. This, in their minds, would foster the eagerness to support the ruling class: Europe has found “the other” in Muslims, in the United States the Mexicans, and in most of the Muslim world Christians or Westerners. In a former democracy such as Turkey, Erdogan believes that to be Turkish means to be a Muslim. In Russia, on the other hand, Putin puts Russian Orthodoxy first, in order to tackle, as he phrases it, Western decadence. In India, a nationalist government ostracizes Muslims by claiming that India is a Hindu nation. And Xi Jinping’s idea of China’s identity is an ethnic-Confucian one.

How Europe will be addressing and tackling the migratory question is crucial. For now, a majority of Europeans may say “it was ok to help once in the Syrian Civil War but that is it.” However, by all predictions, the 21st century will see far more refugees due to climate change and economic pressure in different parts of the world. How will the richer parts of the planet, the developed countries such as South Korea, Japan and Taiwan, react to that? There will be no country, island, or peninsula not effected and confronted with the question how to act in a humanitarian way but also, in these aging societies, how to think about and handle migration in general.

Alexander Görlach is an affiliate professor to Harvard, in the "In Defense of Democracy”-Program of the F.D.Roosevelt Foundation at the College of the University. He is further a senior fellow to the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs and a fellow to the Center for the Research in Arts, Social Sciences and Humanities at the University of Cambridge, UK. Alex holds PhDs in linguistics and comparative religion and is an op-ed contributor to the New York Times and the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. He is the founder of the debate-magazine The European and the publisher of the online-magazine www.saveliberaldemocracy.com. |

뉴스타파는 권력과 자본의 간섭을 받지 않고 진실만을 보도하기 위해, 광고나 협찬 없이 오직 후원회원들의 회비로만 제작됩니다. 월 1만원 후원으로 더 나은 세상을 만들어주세요.