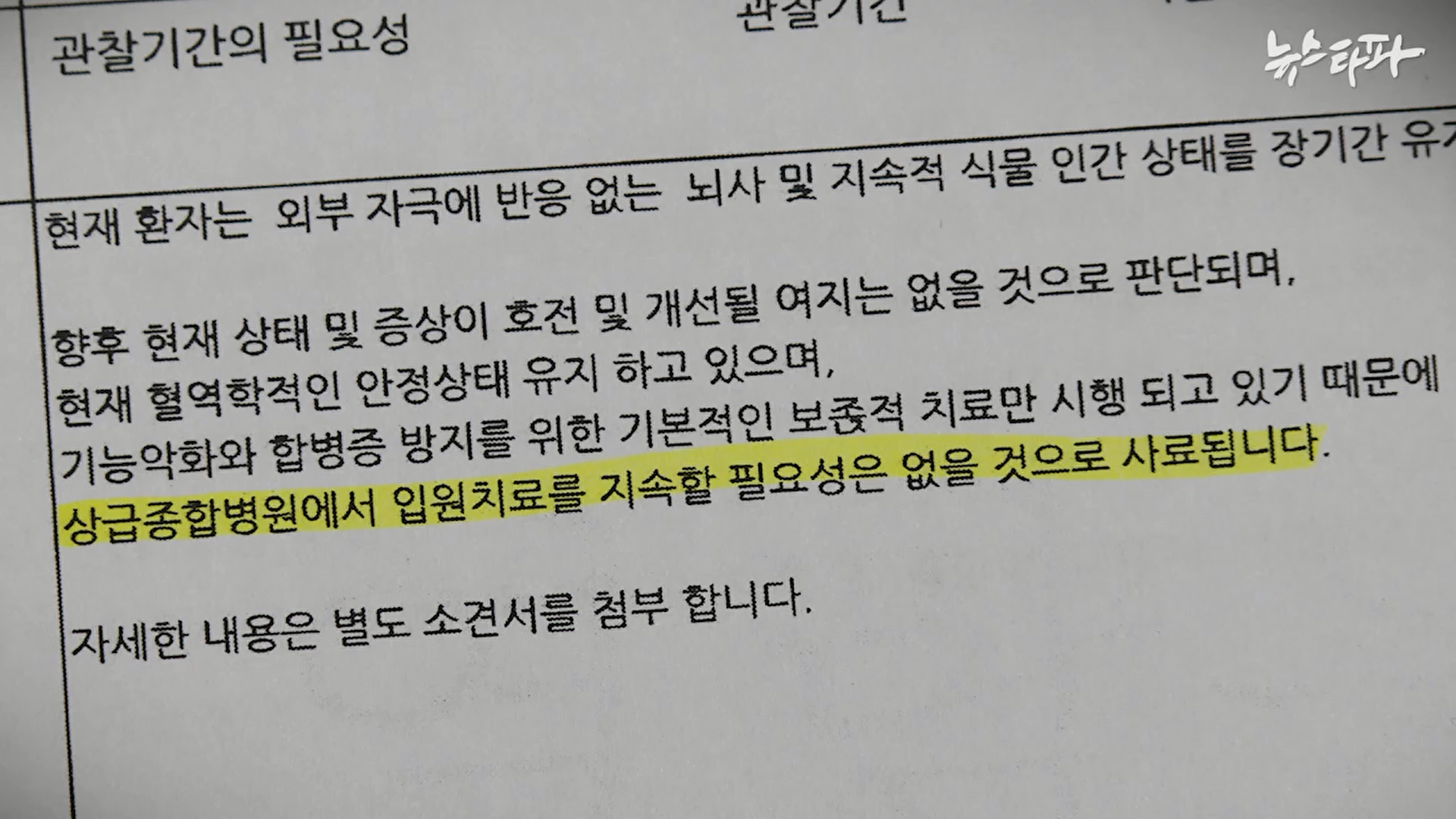

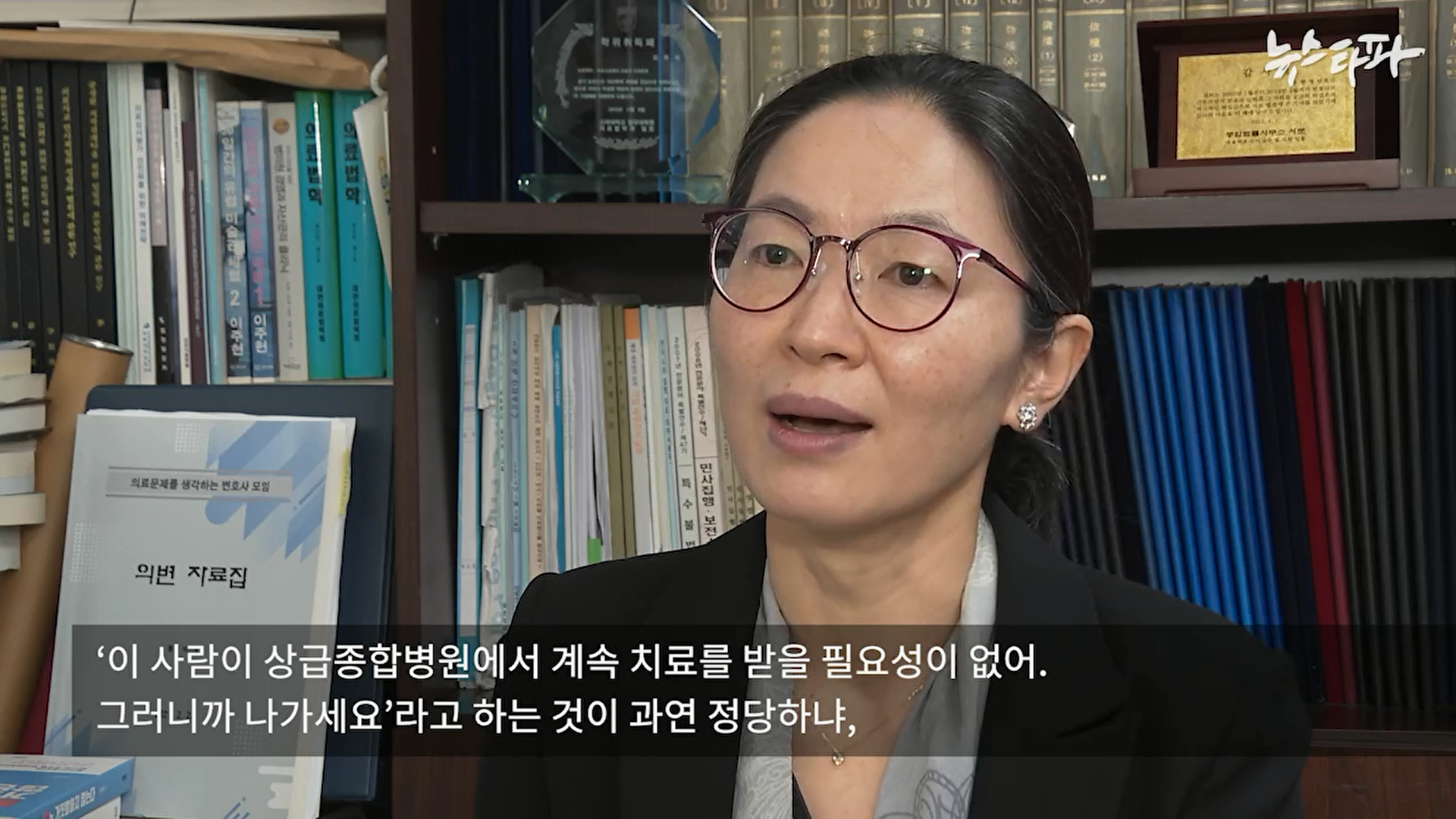

“Not falling under the standard services of tertiary general hospitals according to the Notice of the Ministry of Health and Welfare does not mean that medical personnel can refuse medical treatment or assistance in childbirth, and therefore, the fact that it does not fall under the standard services of a tertiary general hospital or that the treatment is available at hospitals or general hospitals cannot be justifiable for terminating the medical contract.”Judgment of Cheongju District Court / No. 2016Gadan103132, No. 2017Na15103

“Despite the fact that there is a difference in medical services between a tertiary general hospital and long-term care hospital or hospital, theoretically it can be said that there is no difference in conservative treatment between a long-term care hospital and a tertiary general hospital but it seems necessary to consider whether there isn’t actually such a difference or whether patients’ doubts or anxiety are vague and baseless."Review of 2018 Major Medical Decisions / The Korean Society of Law and Medical, 2019

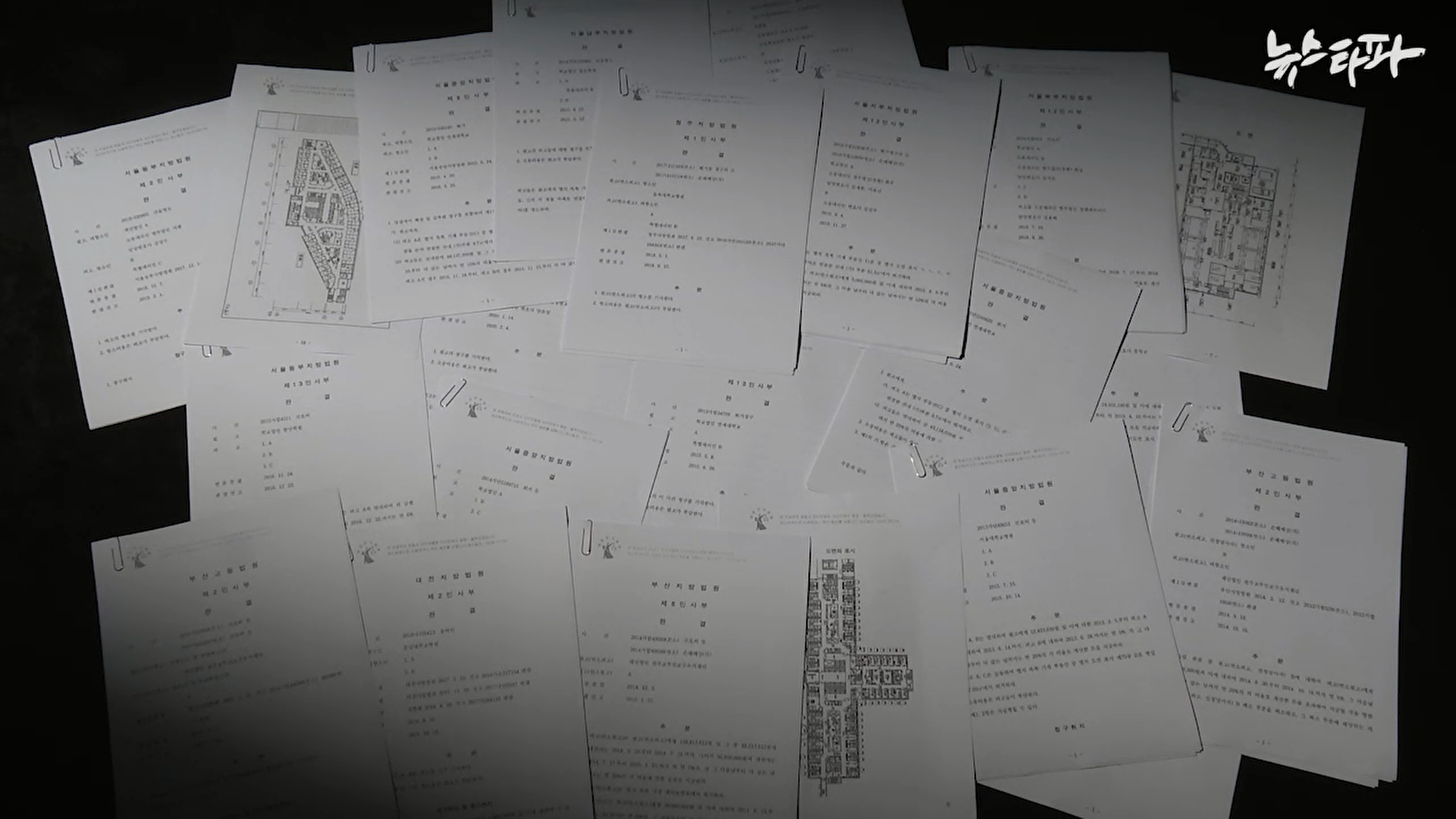

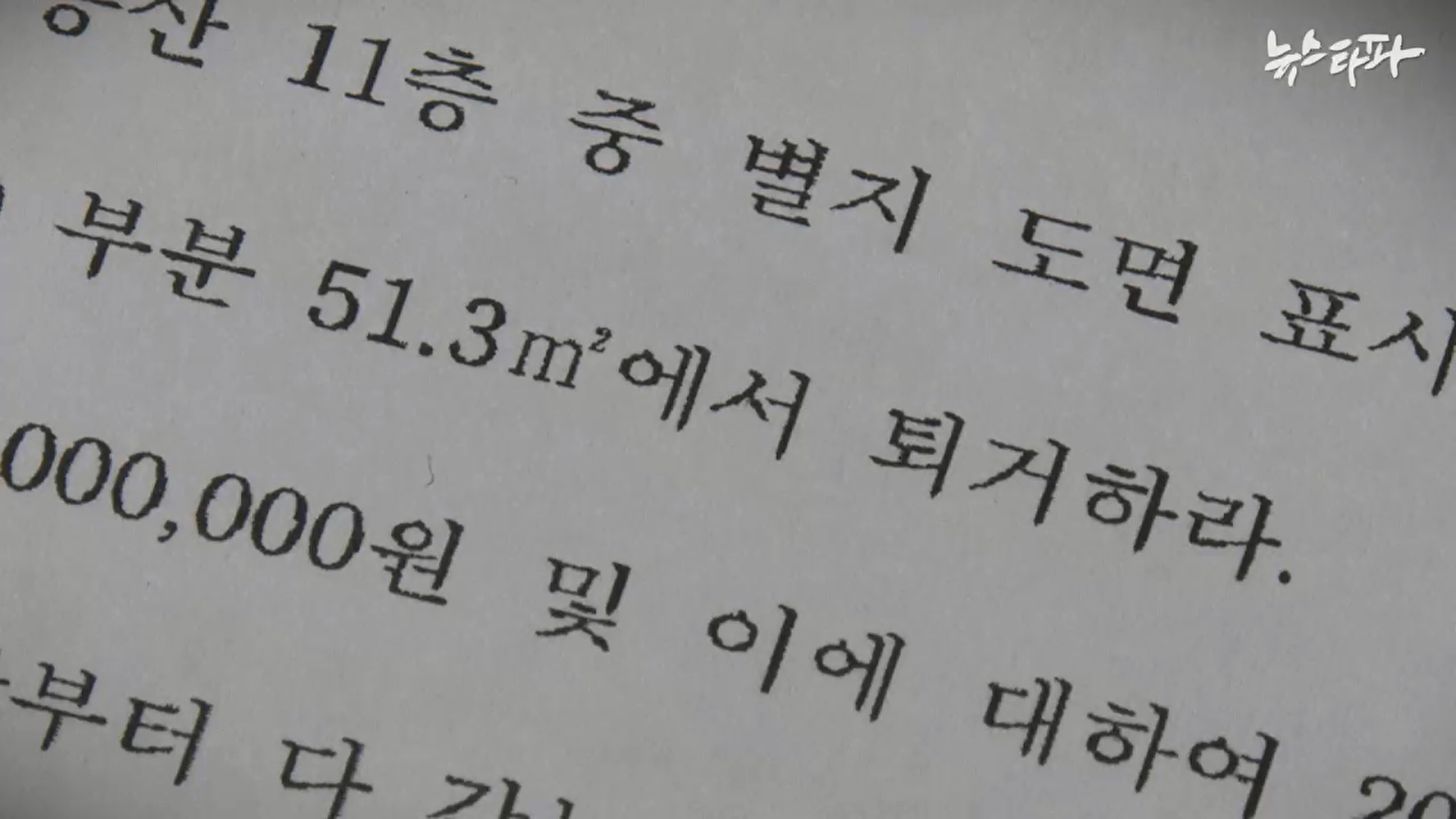

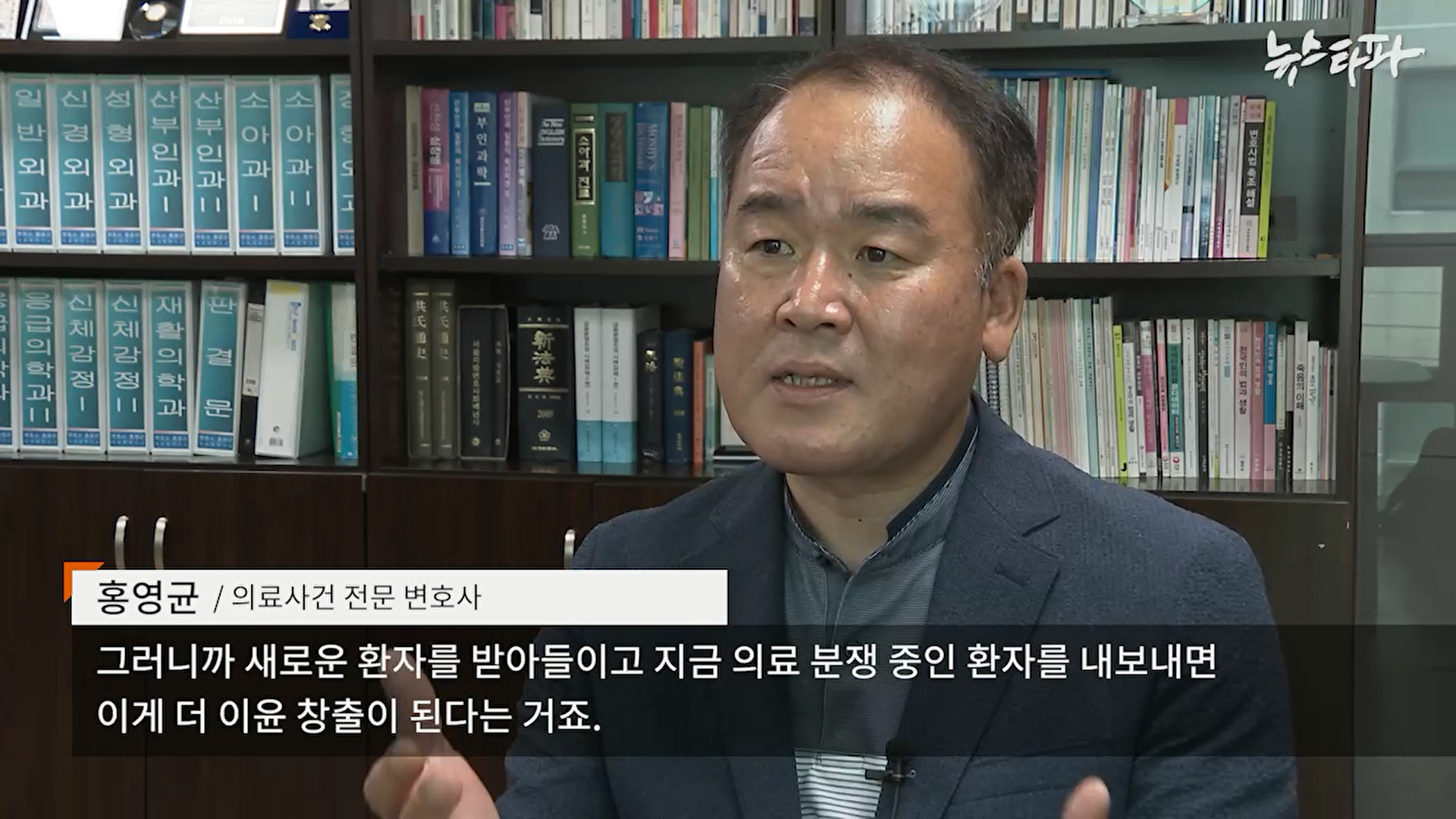

“Inpatient treatment in a tertiary general hospital is a socially limited medical resource which requires to be utilized and distributed more efficiently for the public welfare to meet the above purpose. In this regard, when determining whether there is a justifiable reason for a tertiary hospital to request discharge of a patient by terminating the inpatient treatment contract, it should be based on whether the patient continues to require inpatient treatment at the level of a tertiary hospital, not the need for the patient to continue receiving treatment but… It seems that Asan Hospital would have had a lot of trouble with the hospitalization and treatment of severe acute-stage patients who can only be treated at tertiary hospitals as Jang does not leave the hospital.”Dec. 2021, Seoul High Court, No. 2021Na2021065 / Court ruling for eviction claim of Asan Medical Center vs. Jang Gyeong-bok

“Simply put, it means that you are hopeless and suffering a lot, but because you are refusing to be discharged, one who is more ill or could be treated cannot be hospitalized. So, you should go. It sounds like this and it’s very cruel. We go to a hospital because we are ill and they should say that the patient can no longer be treated. But what we understand, it’s like saying, ‘Now we don’t need to treat him. there is no use for us.’ It breaks my heart.”Jang Won-jae, Son of Jang Gyeong-bok

| Reporting | Hong Woo-ram, Kang Hyeon-suk |

| Video Reporting | Kim Ki-cheol, Jeong Hyeong-min, Shin Young-chul, Lee Sang-chan |

| Video Editing | Park Seo-young |

| CG | Jung Dong-woo |

| Design | Lee Do-hyeon |

| Web Publishing | Heo Hyeon-jae |

KCIJ-Newstapa does not accept any advertisement or commercial sponsorship. Individual citizen's voluntary support sustains Korea’s only independent investigative newsroom. You can join our 'Defenders of the Truth' now.